I read this book about 11-Jun-2014. I've read this book before. The book is copyright 1950. This note was last modified Friday, 13-Jun-2014 20:37:13 PDT.

Again we have the resource-starved world, exemplified by food rationing in North America. However, his Boy Scout troop does visit Antarctica, and there's reference to other travel. Plus of course Earth is colonzing many planets, and is about to start one on Ganymede. The green revolution was not expected, and neither was the increasing rather than decreasing cost of power. (This one is from 1950).

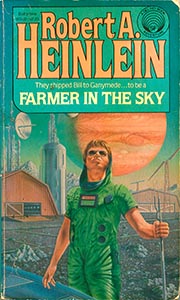

This cover has one of the ugliest human faces I've ever seen on

it. On the other hand, "Lermer" is one of those Heinlein names for

villains; it's weird he landed it on the hero of this book. The face

looks right for a "Lermer".

This cover has one of the ugliest human faces I've ever seen on

it. On the other hand, "Lermer" is one of those Heinlein names for

villains; it's weird he landed it on the hero of this book. The face

looks right for a "Lermer".

This is the one where he flummoxes the chief engineer of the Mayflower with his question about what happens when you apply more power near the speed of light. They even explicitly say that the math is complex (grammar school calculus isn't good enough). Actually, the math is simple (the experiments to show it's accurate are sometimes kind of subtle, or at least very precise). The energy needed to accelerate each little bit more goes up fast; you divide by zero trying to get to light speed.

We have a couple of the stupid, ignorant, entitled women early on, asking their husbands for the impossible. It's a Heinlein trope, in between the strong, empowered women (and not even that split by time; Peewee is fairly early, as is Hazel Meade Stone). And it's obnoxious; I don't know actual women like that, it seems like a misogynist stereotype.

Billy's father has now (p. 69) twice pointed out big holes in his information, first that the pilot of their shuttle ship really had been captured by pirates (he hid in a cargo pod on a ship expected to be attacked to help catch them), and second that torch ships needed a chief engineer (the job includes being the sacrificial person who goes in and makes adjustments and then dies, if things get that messed up). Not sure I approve of a design that requires such a person.

They're singing (with Billy playing his accordion) The Green Hills of Earth. I suspect Heinlein was really proud of that song. Hmmm; I wonder when the words first appeared? I wonder if he's referring to it long before it actually existed? The story "The Green Hills of Earth" wasn't published until the year after this. (The idea, and indeed the scansion scheme, appeared in "Shambleau" by C. L. Moore. Her lyrics and Heinleins can be combined, they fit the same tunes.)

Sex discrimination has come up a couple of times. Peggy wanted (p. 51) to get a tour of the control room the way Billy did, and her mother says "Billy is a boy and older than you are." Which Peggy declares unfair, and Billy agrees in his head that it's unfair (but then goes on to think that life generally is pretty unfair). Peggy's mother doesn't really have any idea how Billy got a tour; in fact he and his friend just knocked on the door. Later, Billy teaches Peggy to play cribbage, and she "pegs a pretty sharp game for a girl". I don't know if that's supposed to be normative, or if we're supposed to notice Billy being prejudiced (this book was published in 1950, remember). He's also dismissive of the girls starting their own scout troops, and asks "Why do girls copy what the boys do?" I feel like we're being told about issues he has, but it still could be intended to describe "reality".

I'm amused that he explains that they took the trouble to dodge the asteroid belt, though the older less powerful ships went right through it, because it made the captain feel safer. It's the preamble to the story of their getting hit by a meteor. I guess you can't really have a 1950s book about space travel without being hit by a meteor. Right between Billy's feet, as he's standing at his bunk. He's properly scared when the air-tight door closes, sealing them in. I mean, he understands the necessity, but he's on the wrong side of the door. But he stuffs his Scout uniform in the hole, and then a pillow (foam rubber, less porous), and tells the Captain what's up on the intercom; he does what's necessary, without too much opposition from the other kids in the dormitory.

They don't armor the ship more heavily because the human body isn't harmed by primary cosmic radiation, but is by secondary and lower; so more armor would actually make it more dangerous. I believe that one is just completely wrong. Not totally sure which parts. It looks like the terminology has remained consistent, and we're still somewhat unsure of the original sources of cosmic rays. ("Rays" is traditional but inaccurate terminology; they're subatomic particles with mass, not photons.)

Here as well as in Space Cadet they use "flicker lighting" to help the plants grow in hydroponic farming. I don't think that one worked out.

They've actually messed with the basic time units on Ganymede! Their minute is about a standard second longer than an Earth minute. I think all the reasons other colonies don't do this are pretty good—and, after all, Ganymede has three-and-a-half days of light and then three-and-a-half days of dark (at least in this book); you can't make most time units come out sensibly anyway. Bill says only scientists would care, but I think lots of kinds of technologists would, and maybe cooks, too (one in sixty won't be enough to change a lot of recipes, though). He doesn't talk about the problems of getting special local watches made, either. Given their dependence on Earth for manufacturing that would be a big deal!

Some of the lyrics for "Green Hills of Earth" are here, too (p. 159). "Out ride the sons of Terra; Far drives the thundering jet—" also "We pray for one last landing on the globe that gave us birth—".

"You know, the Eskimos have a saying, 'Food is sleep'." This is a fannish truism applicable to surviving an SF convention; I wonder if we got it from here (p. 192)?

And here on p. 196 is one of the great memes of science fiction (up through at least the 70s, but too many authors are still using it), which turns out to be simply false. "The basic theorem of population mathematics to which there has never been found an exception is that population increases always, not merely up to extent of the food supply, but beyond it, to the minimum diet that will sustain life...." First, the idea of a "theorem of population mathematics" is nonsense. It's assigning mathematical rigor to something about the real world, which is always a mistake. Second, both the "green revolution" and the "demographic transition" came along, and we have more people and less starvation than Heinlein expected. Of course, 1950 is before the pill and before Roe vs. Wade; to some extent before America got very far with empowering its women, which is apparently what drives the demographic transition (though they had the vote, could own property, many even got quite a lot of education). (That emphasis in the quote is in the original.)

And the demographic transition isn't as new an idea as I had thought; looks like it started up in 1929. I wonder why the Malthusian catastrophe was so beloved of SF writers?

Kind of sad that Peggy had to die to avoid a tragic ending.