Turns out physics is (more and more) setting performance limits on digital cameras. (Title is a reference to the controversial Tom Godwin story “The Cold Equations”).

I’ve been maintaining two camera systems for a while now—Nikon, and Micro Four Thirds (my bodies have all been Olympus). That developed sort-of accidentally; I got an E-PL2 to replace a Panasonic LX3 as my “point and shoot”. But of course, over time, lenses accumulated, and it started to be a significant camera for more than just snapshots. And when I upgraded to an OM-D EM-5 it was pretty good at video, too (most of my work on the Cats Laughing reunion concert at Minicon 50 was done with it). And after the body upgrade it became my main camera, except for sports action (almost all roller derby) and nasty low-light (often music in bars).

Having both systems leads to having the wrong one, or carrying both, on trips. And to ongoing expenses. And a certain level of duplicate lenses. And to having only a single body on either side.

And, just recently, the OM-D EM-5 body has packed it in (“beyond service life” according to Olympus service). This kind of brings the question of just what the heck I should do to a head. Without spending too much money, of course.

The Nikon gear (both what I have, and the models I might buy) is an old-school DSLR. Viewing is optically, through the taking lens, via a pentaprism and a moving mirror, which means I have to line my eye up with the lens to see anything (crawling on the ground or whatever as necessary), and that in low-light situations it can be hard to see. It also means manual focus is hard, since the view can be dim and the focusing screen is not optimized for manual focus. Auto-focus is by phase-detect sensors in the bottom of the body, fed by semi-transparent spots on the moving mirror plus pivoting sub-mirrors on the back (how does that ever work?).

The Micro Four Thirds gear is of the more modern “mirrorless” design. There’s no big mirror flapping around to make noise and cause shake. Older models including my dead one use contrast-detect auto-focus based on the data from the main image sensor; some more recent ones like the OM-D EM-1 mark II and the Sony A7R II integrate phase-detection AF sensors on the main sensor, making AF much faster (phase-detect sensors tell it which way to adjust, contrast detection does not, among other issues).

Watching the development of cameras over the last decade, I think I see that we’re past the time for silly flappy mirrors. I’m starting to feel about them a little like the way Heinlein described internal-combustion engines in The Rolling Stones:

The prime mover for such a juggernaut might have rested in one’s lap; the rest of the mad assembly consisted of afterthoughts intended to correct the uncorrectable, to repair the original basic mistake in design—for automobiles and even the early aeroplanes were “powered” (if one may call it that) by “reciprocating engines.”

A reciprocating engine was a collection of miniature heat engines using (in a basically inefficient cycle) a small percentage of an exothermic chemical reaction, a reaction which was started and stopped every split second. Much of the heat was intentionally thrown away into a “water jacket” or “cooling system,” then wasted into the atmosphere through a heat exchanger.

What little was left caused blocks of metal to thump foolishly back-and-forth (hence the name “reciprocating”) and thence through a linkage to cause a shaft and flywheel to spin around. The flywheel (believe it if you can) had no gyroscopic function; it was used to store kinetic energy in a futile attempt to cover up the sins of reciprocation. The shaft at long last caused wheels to turn and thereby propelled this pile of junk over the countryside.

Apart from the risk of simply being completely wrong, I’m wondering if it’s too early to go all-in on mirrorless designs. The main players are Olympus and Panasonic (in the Micro Four Thirds collaboration) and Fuji. Canon and Nikon have minor lines of no particular market or technological significance (though rumor has it that Nikon is coming out with a full-frame mirrorless line next year), Leica makes a few full-frame models at Leica prices, and Sony has some very interesting full-frame models (but the lens lines for them are limited and pretty expensive).

Oh, and there are some medium-format mirrorless models now, from Leica, Hasselblad, and Fuji at least; those aren’t oriented towards sports-level action, and are getting into five figures instead of mid 4 in price, so they’re not anything I should or can think about.

Mirrorless cameras are very easy to adapt to use any old-style SLR lenses (and many others), in strictly manual mode. Because they don’t have to have space for a mirror to flip up, the back of the lens mount flange is very close to the sensor; and when making an adapter that’s one of the inescapable limits (the other is the coverage of the lens being adapted). And, with electronic viewfinders and modern technology like “focus peaking” and just magnifying the image, manual focus is vastly more usable than it was with SLRs. I do still need AF for fast-moving subjects, though, especially sports, and it’s convenient some of the rest of the time. However, my current mirrorless camera wasn’t modern enough to have focus peaking, so I don’t have more than passing direct experience with it (playing with other people’s cameras).

While I lived with film for decades, I now casually expect modern levels of low-light sensitivity out of my equipment (and I am, after all, mostly competing with people who either have it, or don’t want it). Micro Four Thirds uses a sensor half the area of a “full-frame” sensor. The Fujis and the Canon are APS-C. The bigger sensors will always capture more photons per pixel at any given resolution (each pixel is simply physically bigger). And while they’ll all get better at capturing, and at processing the data they capture, they’ll all be reasonably in step on those improvements. Bigger will always win.

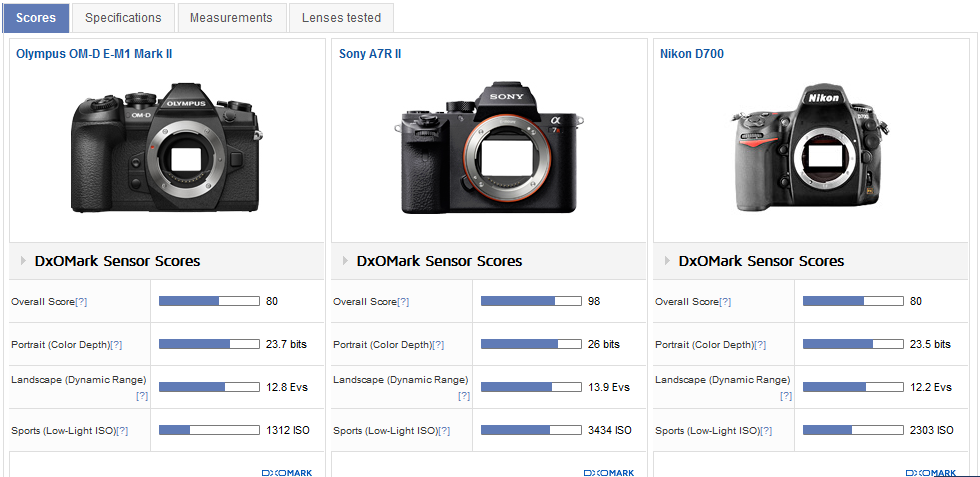

Here are the DXOMARK stats on some of the cameras I have or am considering:

My old Nikon D700 has a “sports” score (which is basically high ISO quality) of 2303. The fancy new OM-D E-M1 Mark II has a score of…1312; not that much better than half as good. And the Sony A7R II, one of the very top low-light cameras, scores 3434. In the nearly 10 years since my D700 was released, sensors and processing haven’t improved enough for any smaller sensor to catch up with it, but sensors the same size have moved well past it. So the latest fancy Micro Four Thirds body would be a considerable step backwards in something I care about (possibly mitigated by a lens a stop faster from 200mm to 300mm, see below).

Just to confirm the DXO methodology, here are lab test shots of some of the choices from dpreview.com:

(Note that the Nikon D750 is considerably more recent than my D700; but they didn’t have anything that old in the database, not even the D3).

That’s kind of interesting, in that the Sony doesn’t look as good as its rating would suggest. The E-M1 Mark II does look somewhat better than the E-M5. And of course the D750 beats them all, but that’s a modern full-frame DSLR.

Going solely to any mirrorless system requires buying some high-end lenses, too; at least their 70-200mm f/2.8 equivalent. And there, Micro Four Thirds wins big; the Olympus equivalent (40-150/2.8 Pro) has equivalent angle of view of an 80-300, which is enough longer to be very nice (a stop faster anywhere beyond 200mm equivalent than anything I have now), and costs “only” $1400. The only choice for the Sony (no Sigma or Tokina models available) costs $2600.

Oh, and there are some fairly significant Olympus rebates and trade-in deals for the next couple of weeks.

Decisions, decisions!