Or, for those not from this part of science-fiction fandom, just think of it as some rather challenging scanning and OCR issues. (Read about APAs.)

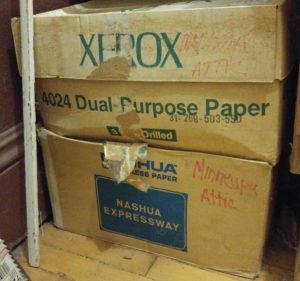

I sorted through three boxes from upstairs and got this:

And there are four more boxes up there waiting.

Now, there is probably a lot of duplication (mine plus Pamela’s copies).

Minn-StF owns an Epson duplex auto-feed scanner, which is kind of tailor-made for this job (“duplex” means it scans both sides of the sheet in one pass through). And it’s amazing how good we’ve gotten at handling individual sheets of paper using just a few plastic rollers. Still, when the paper is 40 or so years old and the stack includes many different kinds of paper intermixed, it can be a challenge. (Most Minneapas had at least offset paper, mimeo paper, ditto paper, and often twilltone. And the covers are sometimes card stock.) Luckily, restarting after a jam is easy, so long as you didn’t let it reset the page numbering to 1 automatically.

I made some test scans at 300 dpi and 400 dpi, and tried saving them as JPEG and TIFF files. The scanner was nearly twice as fast at 300 dpi than at higher resolutions, so I left resolution there. I was pleased, though a bit surprised, to find essentially no visible JPEG artifacts (at 80% quality) on all this text. You’re seeing a lot of the paper texture at full res, and it’s enough to satisfy the OCR software…and the JPEG file is 2 MB or less, the TIFF is about 34 MB. So I actually stored the images as JEPGS. (Nearly 5000 pages from Saturday’s session, looks like; which was one of those three banker’s boxes.)

Many pages show some browning around the edges. It’s interesting how much variation there is among the different kinds of paper people used.

The print density and clarity varied quite a lot to begin with, as I remember. It certainly varies a lot today. Here are some examples at 100% size.

OCR of this sort of material ranges from chancy to hopeless. The volume involved is such that no real quality control or proofreading pass on the OCR is possible, either. However, by using a clever PDF feature we can produce “PDF/A” files which, when opened, show you the image of the page, but when searched by the computer let it search the OCR output (including the images of every page does make the files big, though). Even when OCR is bad, it catches words correctly a lot of the time, so searching for a name or a topic keyword will find you many of the references. And important words in a discussion tend to be repeated, so you’ll be brought to most of the pages the discussion occurs on. (My OCR work on this is being done with an old version of ABBYY Finereader.)

There are legal and privacy issues that make it unlikely that the collection of scans will be posted publicly. They may well be available to people who were in Minneapa. Scanning them gives us backup copies and protection against further deterioration, and some convenience for some people with access to the collection.

Anyway…17 down, 383 to go!