Mike Johnston at The Online Photographer recently posted an article about not switching camera systems, which was sparked by Thom Hogan’s article on the topic. Very very briefly, Thom is suggesting that all the systems have gotten so good that most of the old semi-decent reasons for switching no longer apply to most photographers.

This is not obviously stupid.

And it got me thinking about my camera system switches. Several of mine can be described at least as unsuccessful (not always for reasons I should have anticipated though).

So, let’s see.

First Camera

Around 1962 (I have negatives dating from that school year) I was given a Tower Pixie 127 camera, for my birthday or perhaps Christmas. I had little input on this, and didn’t know anything about cameras, and had no previous camera, so this is not in any sense a switch. But that’s the baseline.

First 35mm Camera

I was given my mother’s old Bolsey 35 in 1966, before we went over to Switzerland for a year. It had become surplus when my mother got a Minolta fixed-lens rangefinder camera with a light meter in 1964, before our summer trip to Uganda (my father was going there to work on a project writing mathematics textbooks for the English-speaking countries in Africa).

Again, I had little input (though I could have ignored the camera). It doesn’t tell my much about my system switching behavior.

I soon bought a little light meter for it (a Biwi Piccolo, bought in Karlshafen am Weser), and shot some Kodachrome slides with it as well as B&W negatives.

This camera eventually lead to my starting to do my own darkroom work, a couple of years later, so having a 35mm camera was important.

First SLR

This was all my choice, and did represent acquiring a new system (I didn’t lose the Bolsey; though I didn’t use it much any more). I chose a Miranda Sensorex with the 50mm f/1.4 lens. Largely, I chose this because they got the highest ratings in Consumer Reports review of SLR cameras.

Getting a serious interchangeable-lens camera was certainly the right choice for me at this point. In the next few years I acquired a Tamron 200mm f/3.5 lens and a 28mm (going both longer and wider than the usual choices at the time). I took a lot of photos with this setup, through high school and into college. This was the camera I wielded for the Norhian, my highschool yearbook, and which I was shooting when I built my own darkroom and started doing all my own B&W printing and processing.

It was not a particularly good choice. One thing I learned from this is that Consumer Reports’ reviews are not really good guides for expert users. While I wasn’t an expert user when I bought it, I was heading that direction, and various limitations became apparent (in range of lenses available, particularly).

Leica

Getting a Leica M3 was an excellent choice. Over the next 2 years I added 90mm Summicron f/2 and 35mm Summicron f/2 lenses, and used them a lot. This was one of my main cameras when working for the Carleton Alumni Publications Office (their full-time professional quit during a hiring freeze so tight that the people who were responsible for a lot of the fund-raising couldn’t replace a key employee; so they ended up using a number of student photographers a lot, including me).

The rangefinder focusing worked better than early 1970s microprism screens for focusing in dark situations, and I did a lot of shooting in the dark (late night parties and music sessions, stuff at science fiction conventions) or by flash in rooms that might be pretty dark. The lenses were faster than the wide and telephoto choices I had previously had, too, which helped. And the non-reflex viewfinder meant I could see the exact moment the flash illuminated, so I had a better idea whether I got the shot than with an SLR.

I’m not sure that I wouldn’t have been as well off getting a Nikon SLR body and f/1.4 lenses, though. I might have lost some on focusing still, but I could have extended out to the 135mm f/2 lens to get a longer reach (I owned that lens later, it’s wonderful). The pricing of Leicas was going crazy, and it became less and less of a viable option for a price-conscious user as things went forward, but I’m not sure I should have known that when I bought the M3.

Pentax Spotmatic

Shortly after getting the M3 I swapped the Miranda for a Pentax outfit, with more lenses and longer ones (out to 400mm).

I picked it specifically as an adjunct to the Leica; I’d be using it for longer or wider lenses than I could support on the Leica (well, than there were frame lines for; I could use wider lenses at least with an auxiliary viewfinder, but then focusing and framing would be separate windows).

Pentax had a wide range of lenses, and very high optical quality in general. I never bought a prime lens for it (it came with such a set I never really moved to add to it; it was a decade later that I went out as wide as 24mm for the first time). Stop-down metering wasn’t particularly a problem, by my standards at the time. This may have been a good choice, at least as a simple swap for the Miranda.

I don’t see this as a mistake, more as the correcting of a mistake. But the more I think about it, the more I think that with 2020 hindsight (okay, I’m 2 years late) my best choice would have been to buy a used Nikkormat or Nikon F first and just stick with that, adding lenses and bodies here and there. Where’s the transtemporal mailbox?

Pocket Instamatic

Don’t worry, I didn’t get rid of any of the other gear.

The technology was hyped and interesting (they gave up on holding the film really flat, and instead calculated the lenses to focus properly on the film as the cartridges actually held it). It was my first step back into a “toy” camera, and I used it for a lot of snapshooting. The small size was convenient, but I never worked with those photos in the darkroom.

This was clearly a mistake. The idea of a “toy” camera, something smaller to keep with me more of the time, was good, but there was no need to step down this far. At that point there were very good small rangefinders like the Olympus 35RC or the Canonet QL17 with f/2.8 lenses and pretty good rangefinders, and light meters or even auto-exposure. I didn’t actually carry the Instamatic in a pocket, so these would have worked as well for carry I think, and much better for photography (and I could use the negatives in the darkroom myself).

The insane choice that keeps attracting my retrospective eye was the Minox system. Much smaller negative, and would have caused darkroom problems for me (the enlarger in my home darkroom was a Durst M35, which supported 35mm only, and had no alternative negative carrier options, so no way to handle smaller formats (or larger), and the darkrooms at college didn’t have such negative carriers in place, though they would have been available for purchase). Probably would have been a mistake, but I don’t know.

Canon AF35M

Then I graduated, and lost access to the college darkrooms, and had no darkroom access. There was a 4-year gap between roll “ddb-396” and “ddb-397”. I regret this gap rather a lot. I could have set up a good enough darkroom in my apartment (Bozo Bus Building basement) and my first house, though it would have required buying an enlarger (since I had sold mine when I got to the good darkrooms at college).

And sometime during that period (not at the beginning) my camera gear was stolen, along with some other stuff, out of my closet at home.

After a while I decided I had to get back into at least snap-shot photography, so I bought one of the new breed of auto-focus 35mm compact cameras (successors to the Olympus 35RC and friends). It was a marvelous toy camera, and I still do things with the photos from it. The idea of a toy camera was, once again, proven good!

Nikon FM

Just a few months after that, I bought a Nikon FM and Nikkor 35mm f/2 and 105mm f/2.5 lenses. The FM had a brighter focusing screen and viewfinder than many older SLRs, and you could get especially bright focusing screens for it (which I did).

My thinking included that I might need to also replace the Leica for low-light work, but I certainly needed to replace the SLR for wider, longer, zoom, and such, so I’d try a modern SLR first before committing the money for the Leica (which during those 4 years had definitely gone up a lot). And in fact I never did replace the Leica, I got more bodies and lenses for the Nikon system instead.

I have no idea why I got the 105/2.5 lens. It’s a classic portrait lens, but what I knew I loved was the 90mm, and Nikon had an 85mm that was available in either f/2 or f/1.4 (nearly 2 stops faster than the 105/2.5). I somehow didn’t know about the famous Nikon 85mm? I would definitely have been better served by the 35/1.4 and the 85/1.4; and then adding the 135/2 rather sooner than I actually did.

Despite that lens selection error, this was one of my best system choices. Nikon was “the photographer’s camera” from the 60s through the 90s at least, and staying with the same lens mount that whole time would have been better for me.

Nikon L135AF

For some reason I got this to replace the Canon AF35M. This was a clear mistake; it didn’t expose as well as the Canon. I don’t recall brand prejudice having anything to do with the choice. Apparently if I’d gotten the L35AF, it would have been much better (at least so Ken Rockwell says).

Olympus OM-4T

This was one of my most carefully considered system switches. And it turned out to be entirely unnecessary (though one of the reasons I couldn’t have anticipated in 1987).

I had been waiting for Nikon to introduce spot metering in their SLR line. Olympus came out with their multi-spot metering. I thought that I could get considerably better slides (which have high contrast and a restricted brightness range, remember) without slowing myself down too much using multi-spot metering to evaluate the scene and pick an exposure that places things in useful zones (not full zone system, since I wasn’t proposing custom development to match the lighting!).

Well, the multi-spot metering worked fine, it really was easy to spot the high and low brightness areas and see them displayed on the bar as I shifted them around with exposure changes—but it didn’t in practice result in significantly better exposures.

I got a pair of these bodies, and lenses from 24mm to 200mm (including a second 24mm lens that had shift, to handle cathedrals and castles on a trip to England).

And then in 1994 (7 years was my longest run in any camera system to that date, to be fair) auto-focus became important, and Olympus completely missed that boat (until much later). The Olympus gear served me very well, but no better than what I’d had before would have, so the switch was not a good choice.

Nikon N90

The N90 was a rather good prosumer body, but it was expensive, first body I bought that was nudging at $1000. Used to be lenses were expensive and bodies relatively cheap, but AF ran the bodies up, and then of course digital ran the bodies through the roof since the sensor and all the electronics were there. Those things also vastly shortened the useful life of the bodies, which most of us didn’t realize immediately. (They’re not repairable without electronic parts from the manufacturer, who don’t keep them available very long. After that it’s scavenging from other dead bodies.)

I rented one, and an AF lens, for the weekend to test whether I really needed AF, and sadly discovered that oh my yes, I got a lot more interesting pictures if I could focus that fast and that accurately. (Frustrating when the camera missed, but it didn’t miss more often than I missed myself.)

I hadn’t succeeded in unloading much of my Nikon gear during that 7 years, so it was fairly easy to slip back into the Nikon world.

So then over the years I added bodies and lenses and flashes and things.

I’d say that this switch back to Nikon as a very good move for me.

Then digital came along; but I did well remaining in Nikon (no system switch); my first DSLR was a Fuji S2, which was a great choice, then a Nikon D200 (maybe should have waited for the D300).

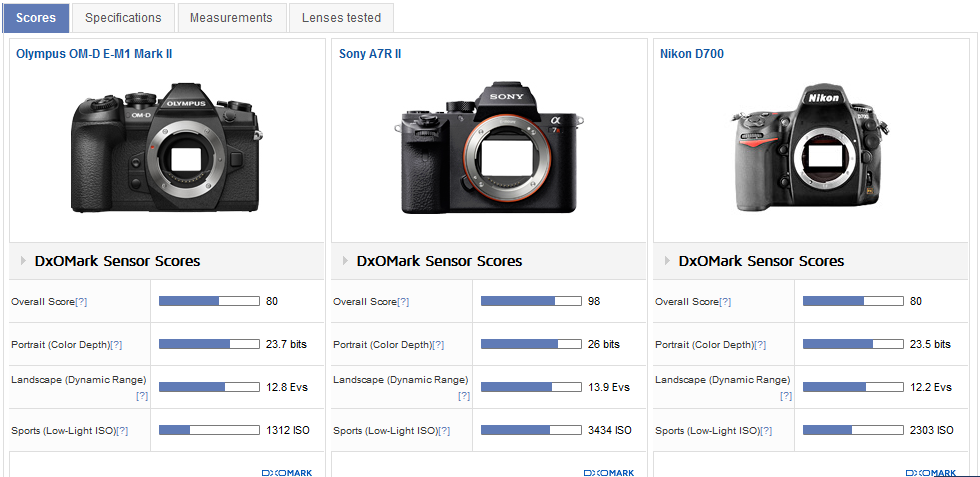

Then a D700, which was the most amazing camera I have ever owned. They put everything I considered valuable from their top-of-the-line D3 professional camera into the D700, plus at least 2 things I valued that the D3 didn’t have (built-in flash that was a CLS controller, and sensor cleaner)…and sold them for half the price of the D3. Mind you, it was still by a factor of 2 the most expensive camera body I ever purchased. I ended up selling a fairly special lens to finance it (but the lens had been better in theory than for me in practice, anyway).

It was a photojournalist’s camera, excellent for its time in low light, excellent AF. Not especially high resolution (it used the big sensor for big pixels). Fit me perfectly.

I thought I’d committed to APS-C format, and had revised my lens collection somewhat, when the D700 hit me, so that was expensive, undoing some lens decisions.

I suppose the change to and then back out of APS-C should almost count as system changes, even if the cameras had the same lens mount.

The D700 was the camera that made my first years of Roller Derby photography practical (light doesn’t look that low, but for action that fast I needed high shutter speeds).

Olympus EPL-2

This started out to be my new toy camera. With the 20mm f/1.7 pancake it wasn’t much bigger than the Panasonic LX3, and was much better in low light.

But it grew on me, or some of the lenses did. Also the video did, and getting the OM-D EM-5 opened up HD video to me fairly seriously; I used that camera for the Cats Laughing reunion concert movie “A Long Time Gone”, as well as for a lot of the still and video work used to promote the Kickstarter and provide the packaging and such.

And then I found myself maintaining two digital camera systems to near-professional levels. On consideration this seemed financially unsustainable, and after kicking this around a lot, I decided that it was time for me to get rid of that old flappy mirror thing I’d been lugging around since 1969, and go mirrorless. I sold off the Nikon gear (I really did sell it all off this time) and and bought an OM-D EM-1 mk II and some more Olympus lenses (the 40-150/2.8 is amazing; angle-of-view of an 80-300 f/2.8, much lighter, and much cheaper).

Fairly shortly after that, Nikon came out with their mirrorless system, and Olympus went through some major restructuring that leaves the photo division in a somewhat interesting position. So…I think this switch was great for me, but the world is rather making it less pleasant.

Conclusions

So, hind-sight certainly has huge benefits over what one knows when actually having to make decisions. I don’t really feel any of my choices were stupid or poorly thought out; the ones that I would like to retroactively improve were largely due to legitimate ignorance really, either in the present or of the future.

Still, it’d be great to send a letter back to myself, long enough to convince myself I had real knowledge of the future. Go Nikon from the beginning. 85mm! Get a toy camera early, but not a super-limited one. Get a Braun RL-515 flash even earlier. Take more pictures of where I live and where I work, especially early computers I worked with.

Oh; and buy Apple, Microsoft, Google, and Amazon in the IPOs.