(Continuing the story of self-publishing a new edition of Pamela’s The Dubious Hills from here.)

This book was written on a computer to begin with, so in the ideal situation we’d still have access to the files with the canonical text. However, this frequently doesn’t work out in cases like this where the book was first published more than 20 years ago.

There are at least three ways this doesn’t work out:

The files may simply be lost.

The files may not be readable with any software we currently have (this could possibly happen even if you’re using the same brand-name word processing program, possibly).

And finally, there may never have been files reflecting the final state of the book. In fact, this is a near-certainty for anything first published in 1994, because at that time the copy-editing process depended entirely on marks on paper. So, unless the author bothered to update the files to reflect changes made at that stage, there never were files with what we really want in them.

Hence the title of this article; we’re going to recover the text for our edition of the book from a printed copy.

There are at least two ways to approach this, but I’ve only ever used one because it’s so obviously best. We could simply retype from the printed copy into some word processor (or dictate it into a voice-typing package). But I actually use the other approach, scanning the pages and then using OCR software on them. I’ve done this more than half a dozen times over the years, and it’s surprisingly easy (I mean, compared to retyping; it still takes a number of hours).

The particular way I did this one bothers some people, I know; it involves destroying the physical copy of the book I scan to save some time and effort (though not as spectacularly as Vernor Vinge does in Rainbow’s End). I’m going to show pictures below the cut; you have been warned!

Yes, I myself do suffer from the delusion that physical books are nearly sacred objects. However, books issued in the modern era in many thousands of copies are very rarely in really short supply; I’m willing to sacrifice one copy of such a book in the service of producing a good e-text, especially since that will contribute to making the book available to a modern generation of readers. If the book were rare or valuable, I’d handle things differently; I’d take the extra time and effort to get a scan (and correct the scan; a good chunk of the benefit comes from a better scan leading to better OCR leading to fewer hours of correction) without destroying the book.

(There are fancy scanners that will scan a book, turning the pages themselves, without even breaking the spine. However, we do not own one. We’re doing this on our own, with outlay of time but only the absolute minimum outlay of money, since we have more time than money at the moment.)

Okay; that cut with the pictures below it coming up now….

The paper in hardcovers (or trade paperbacks) is generally much nicer than the paper in mass-market paperbacks. For scanning, the paper in MMPBs is rough enough to make a difference. Since we have the choice, we’re sacrificing a hardcover—the cleaner scan will lead to less time spent correcting the OCR later.

Basically, I’m cutting off the binding, to give me a pile of individual sheets. This could be done perfectly well with a box knife or whatever and a metal straight-edge, but why pass up an opportunity? Hence, this time I cut the binding off with a radial-arm saw.

This produces a nice clean pile of pages with reasonably consistent margins. These are easier to handle than an entire bound book, especially if you’re trying not to damage the bound book. It’s easier to get the pages straight in the scanner, aligned to the edges right, etc.

Also, I’ve got an ace in the hole here. I’ve got a cute little USB scanner that scans both sides of a page in one pass (Brother DS-720D). It’s manual feed, but feeding all 216 pages into it manually took well under an hour (I think it was under an hour including time spent upgrading the firmware in the scanner and installing its driver software on my laptop). So I only handle each sheet half as often. The next step up from here would be a duplex scanner with automatic sheet feed, and the step up from that is the wonderful automated book scanners [link is video] I’ve mentioned previously.

Found two pages I got the timing wrong on, and wanted to re-scan, but that’s easy; I’m writing out each page image as a separate file, and in fact the filenames contain numbers that happen to exactly match the page numbers this time (I guess I lucked out and started scanning with the same page the numbering scheme called “page 1”). So just re-scan those pages, rename them to match the page numbers, and then replace the previous files of those names.

Next, the OCR! I haven’t used a lot of different OCR packages. However, the one I do use for books, I like a lot: ABBY FineReader. It does the OCR very well, has a really good proofing mode, and will write the output as anything from docx (Office Write XML format) to rtf (rich text file) to odf (Libre Office document format) to PDF/A (archival PDF, with the images shown but the OCR text behind them for searching and copying). Highly recommended (I appear to be a version out of date currently, I’m using V11).

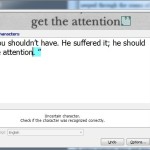

So, that proofing mode. It goes through the files, and shows you each place where it’s not sure it’s right. It shows you the spot in editable text, right next to the image from that part of the scan, with the questionable area highlighted in both. You can click to ignore this spot, add a word to the dictionary, ignore all occurrences of this word, or select from a (sometimes very large) list of possible replacements. (You can configure a lot about this, including color codes for the different kinds of issues it might find; I haven’t found this necessary yet.) It’s also smart enough to identify running heads as just that, and page numbers, and you can then tell it to not include those in the OCR file (that’s what you’ll want if you’re making another book from the file).

Now, note that this isn’t guaranteed to really find all errors; it might not for example be in doubt about something that’s actually wrong. Still, it gets the vast majority of them placed directly in front of your eyes with the text to edit right there handy. It saves huge amounts of time.

Next step, search and replace. I find consistent errors in little things, especially spacing, in the OCR output files, and I find the easiest way to fix them is by using global search-and-replace in my word processor. Things I need to search for and fix include spaces before closing quotes, and nearly every occurrence of two spaces together. What things you find often enough to want to fix this way depends among other things on the font of the book and the printing and scan quality; by the time you’re through with proofing in FineReader, though, you’ll have quite a good idea what they are.

(Speaking of “two spaces”—this brings up the modern fight about whether you should space twice after a period. Everybody taught to type on an actual typewriter does that without thinking about it, it’s really deeply trained in, because manuscript form required it. For typesetting, you do not want to put that much extra space after a period. Depending on your software, whether you type extra spaces may or may not make any difference. Unfortunately fairly often it does, so then you have to get rid of them at that stage if you had them. That’s easy with search-and-replace, though, so no big deal.)

Now, I go into the file and apply styles. Don’t worry about front matter (title page, copyright page, acknowledgments, and such) at this point, we’re worried about the bulk of the text right now. Use styles, not setting local characteristics. Body Text for most paragraphs, Chapter for chapter titles, Poem for poetry, Blockquote for entire paragraphs of quotations, and so forth. (Then, when I do book design, I can just define how each of these is displayed.) And of course clean up anything else I come across.

Always investigate anomalies. Last night (while, I’m ashamed to admit, using an online proofing tool at CreateSpace—so this error had made it through the entire process and was within about a click of being released) I noticed a blank line in the middle of a page. On investigation, I determined that in fact two entire pages of text were missing there. It happened that no sentences were broken, so it wasn’t instantly obvious, but the strange blank line was a valuable clue. Always follow up clues!

Finally, as the last step in preparing the master manuscript file, it’s time to run it by the author (plus any professional or skilled volunteer proof-reader you may choose to employ). If you’re having multiple people edit the file, don’t forget to have them turn on change-tracking mode if you’re all using compatible software that supports such a thing; it automates integrating the results from multiple people.

Proof-reading your own work is very very hard; nobody is any good at it (though some are even worse than others). The author needs to take the last look to actually approve the result, but if you can manage it, either with money or with an appropriately skilled and very generous friend, get a professional to do a proof-reading pass about now.

(Yog’s law—Jim Macdonald’s rule that money flows from the publisher to the writer—is important, and remains true. Schemes where a publisher wants you to pay them are almost invariably scams. However, a publisher needs many expert hands to bring a book out, and if you are publishing your own book you need most of those jobs done too. When you are your own publisher, unless you and generous friends and family members have a wide range of unusual skills, you are likely to need to pay professionals to do work for you. Artists do not work for “the exposure” (at least not if they’re any good), and copy-editors still less (Yog’s law actually applies to them, too). It’s easy to spend more than you can reasonably expect to make on most self-publishing projects just for a professional copy-editing job, which you really need if you’re publishing an original book instead of re-publishing a book whose text is already fixed. Sometimes you have to make do with rather less than fully professional work; for example, I’m designing both the covers and the interiors of these books myself—which will be the subject of a future post.)

This is of great interest to me because I’ve inherited a manuscript that deserves a look from publishers. I’ve got a good photocopy of the typed pages. At some point I have to do a process like yours.